Social distancing and lockdowns are key features of COVID-19 preventative strategy today. For people with access to the internet via either fixed broadband or mobile network, technology is a given. Digital dividends enable an average household to continue life as normal. With good ground infrastructure and logistics,1 the presence of digital infrastructure serves as an economic and social lifeline, facilitating e-commerce for the delivery of food and supplies, as well as working and learning from home. In fact, online shopping has grown exponentially in the United Kingdom, Southern Europe, the United States and China during this crisis.2 Yet the COVID-19 pandemic exposes both challenges and opportunities to reaping the benefits digital technologies (“digital dividends”) offer today to address the pandemic. This article presents three key observations.

First, diffusion of digital dividends remains limited.

Several research studies have found that an improvement in internet and mobile penetration is associated with an increase in output and employment.3 The digital economy is estimated to be around USD11.5 trillion in 2016, equivalent to 15.5 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP), and grew two and a half times faster than global GDP during the past 15 years.4 It is expected to rise to 25 percent of global GDP by 2025 and create new economic opportunities. However, only half of the global population has access to the internet with access dropping to less than 30 percent in parts of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Among the regional members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), nearly 2.4 billion people do not have access to the internet, with majority of them residing in India, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Philippines. Consequently, many of these countries would find it difficult to leverage digital technology to overcome the economic hardships caused by lockdowns and social distancing, and access basic goods and services.

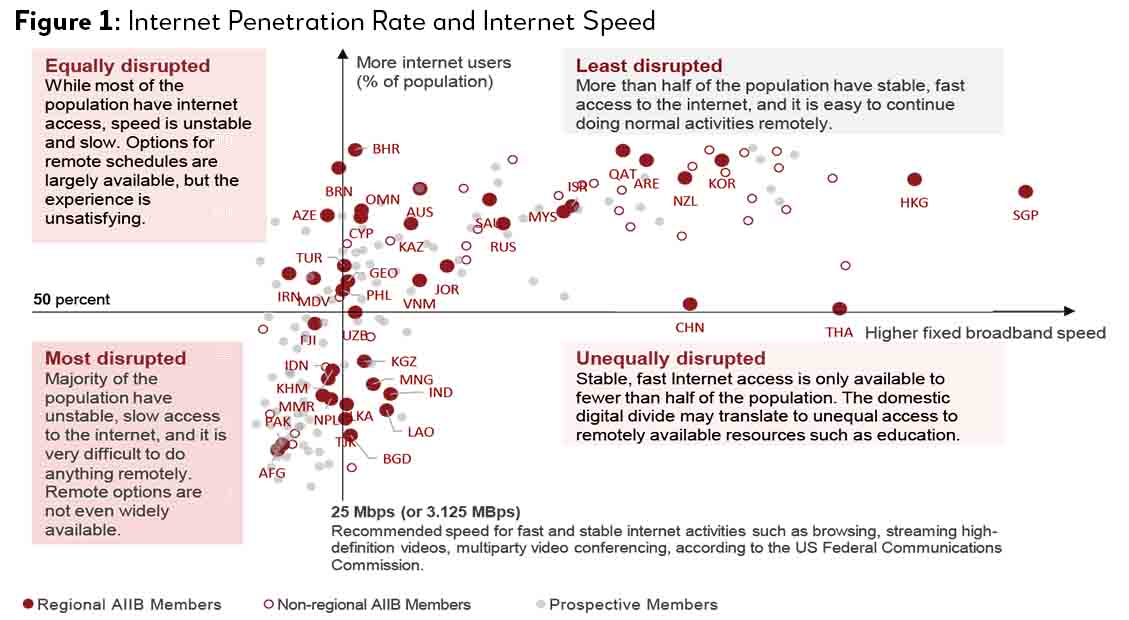

Mbps = Megabits per second; MBps = Megabytes per second.

Notes: Internet Penetration Rate is measured by the percentage of individuals who have used the internet (from any location) in the last three months. The internet could have been used via a computer, mobile phone, personal digital assistant, gaming console, digital television, or other devices. Access could be via either a fixed or mobile network. The three-letter codes in Figure 1 refers to the ISO code for countries/regions in the world, available at https://www.iso.org/iso-3166-country-codes.html. The membership status of AIIB members is available at https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html. Data Source: Internet speed is from Speedtest’s monthly report of global fixed broadband speed for March 2020; internet coverage is from the World Development Indicators’ data on individuals using the internet (percentage of population) based on a three-year average between 2016 and 2018.

The disparity in internet coverage and quality of service has exposed people around the world to different levels of disruptions in their locations caused by the pandemic. Figure 1 plots economies by fixed broadband internet speed and overall internet penetration, illustrating four scenarios they are facing during the outbreak, as remote work or school arrangements mostly rely more on broadband internet than mobile internet connectivity.5 For example, people living in economies in the top-right domain (least disrupted), such as Singapore and the Republic of Korea, may be least affected by lockdowns because they can easily opt to work or study remotely with fast and widely available internet. In contrast, majority of residents in the bottom-left area (most disrupted) may find remote schedules most difficult as the internet there is slow or just unavailable. Large-scale lockdowns may disrupt their economic activities entirely.

For countries in the bottom right, the internet is relatively fast, but it remains a privilege to only a small share of their population (unequally disrupted). The digital divide in these countries may translate into divide in access to many resources such as remote work opportunities or online schooling. The fourth scenario, which are faced by countries in the left-top domain, is where most people have access to the internet though the speed is not high. In this situation, options to work or study online are available to majority of residents, but the user experience is not satisfying (equally disrupted). Social distancing measures hence disrupt majority of the people to a similar degree.

Most low-income economies fall into the first three scenarios where their citizens are equally, unequally or most disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic due to various limitations in access and adaptation to remote arrangements. All this data suggests that costs for timely information run high for the poor, as they may need to wait for information to arrive informally rather than firsthand and in real time.

Second, there are digital divides within countries.

Access to digital infrastructure may differ depending on gender and income. Generally, women are less likely to have digital access than men, whereas low-income households have lower digital penetration rates than richer households. Some of the reasons for such disparities include higher digital entry barriers for women (e.g., who may face discrimination in signing up for a mobile subscription in patriarchal societies) and poor households (e.g., who may lack identification requirements to acquire a mobile phone) as well as geography (e.g., poorer households are more likely to live in less digitally connected areas).

Within a developing country such as Bangladesh, for example, 32 percent of males have access to mobile money accounts compared to 10 percent of their female counterparts. Yet, a similar observation can be found even within developed economies although the differences are narrower. In Singapore, 11 percent of males have mobile money accounts compared to 8 percent for females. In Chile, 21 percent of males have such accounts compared to 16 percent for females.6

Income gaps within countries are likewise correlated with differentiated access to digital technology and consequently, one’s ability to self-isolate and work from home during this pandemic. In the United States for example, one study7 found that the presence of high-speed internet in certain areas enabled individuals to self-distance during this lockdown period. The same study also found a strong correlation between high-income areas and home internet access, thereby pointing to the digital divide between high-income and low-income areas. Another survey8 found that less than 10 percent of the poorest 25 percent could work from home, compared with over 60 percent of the richest 25 percent.

Apart from income, digital access can also be correlated with the types of jobs workers engage in, and this has consequences on how one can continue a normal working life during this pandemic. For example, there is a higher likelihood that people whose jobs require them to sit in front of a computer (e.g., finance) can work from home, compared to those whose jobs require them to have face-to-face interactions (e.g., transportation or utilities).

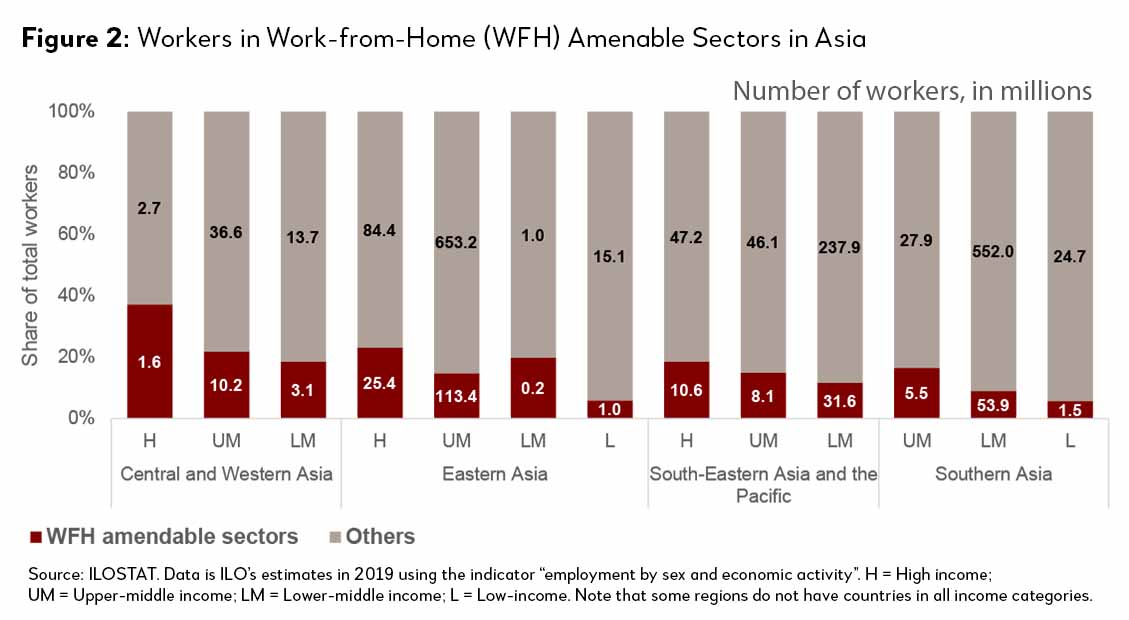

Across countries in Asia, majority of the employed population are working in sectors that require face-to-face interactions, as shown in Figure 2. But richer countries tend to have more workers in work-from-home (WFH) amenable sectors, such as education and financial services.9 Countries in Central and Western Asia seem to have the highest share of workers in these WFH-amendable industries, whereas in Southern Asia, this share seems to be the lowest.

As this data shows, not all would benefit from the digital dividends in a country equally. This is why to invest well in digital infrastructure, understanding its implications across different demographics—income group, gender and occupation—is as crucial as identifying where it is needed the most.

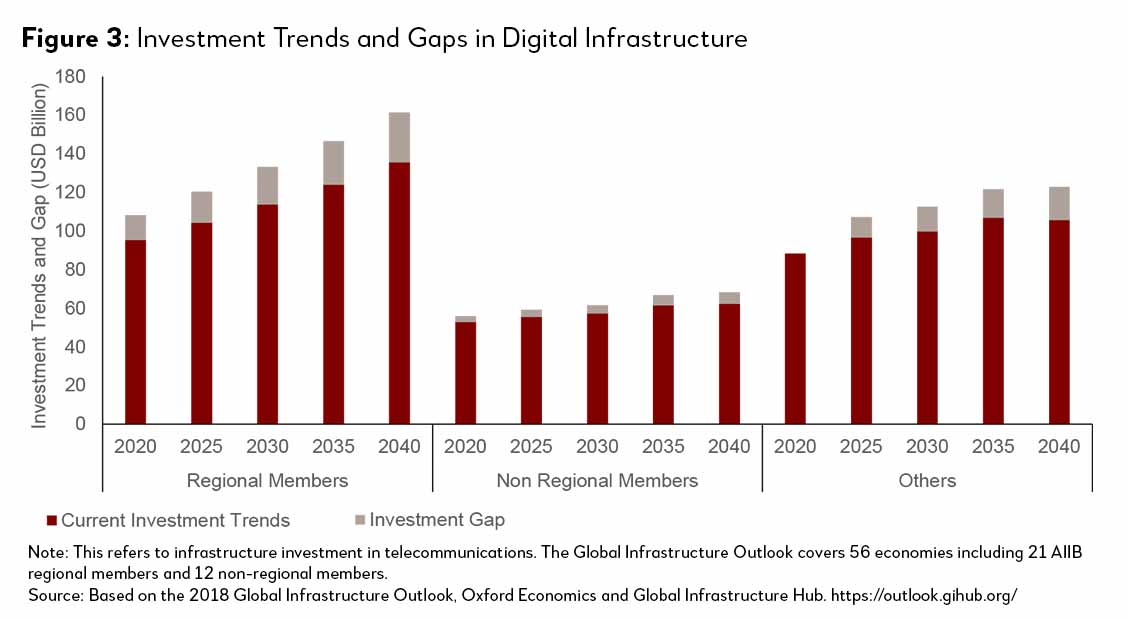

Third, there is a trillion-dollar digital infrastructure investment gap.

To ensure the digital inclusion of underserved people, significant investment in digital technology, including digital infrastructure, is required. According to the Global Infrastructure Outlook, digital infrastructure financing need between 2020 and 2040 is estimated to be around USD6.5 trillion with an investment gap of USD768 billion. Much of this gap resides within AIIB regional members that together account for 53 percent of the investment gap or around USD407 billion (Figure 3). AIIB’s non-regional members account for another 12.1 percent of the overall investment gap, amounting to USD93 billion.

The investment gap is driven by factors on the demand and supply side of the projects as well as regulatory issues. Demand for digital infrastructure investment is curtailed by revenue pressures on operators reducing capacity to invest, lack of awareness among digital companies and lack of skilled technical personnel for the construction and operation of new digital technologies and infrastructures. Supply side inhibitors include a dearth of public investment, lack of investment from multilateral development banks, limited investor capability, lack of financial innovation and a short-term investment time frame. Finally, regulatory bottlenecks have led to a deepening of the digital divide between rich and poor countries and between urban and rural areas. These bottlenecks include poorly structured spectrum licensing schemes that limit market entry, foreign ownership restrictions, high tax rates for digital services and equipment, lack of investment in technical skills, and weak cybersecurity, data protection and privacy regulations.

Recognizing the importance of digital economy in fostering development and the widening investment gap among its members, AIIB seeks to partner with its member countries to strengthen the development of the digital economy and with it, the underlying digital infrastructure. By reducing the carbon footprint, lowering operational costs, minimizing the use of renewable resources and increasing transparency, digital infrastructure complements AIIB’s core values of “Lean, Clean and Green”.

To achieve this, a two-pronged strategy can be considered. First, as elaborated in the Draft Digital Infrastructure Strategy,10 AIIB can support investments in both hard and soft infrastructure. While hard infrastructure involves physical assets needed to establish the connectivity (e.g., such as those for transport, storage, processing and storage), soft infrastructure covers the architecture that connects the hard infrastructure and the technological applications and services needed to operate the digital ecosystem. Second, in partnering with members to finance traditional infrastructure, AIIB can include components of digital technology to improve the development outcomes. Applying digital technology to the construction of traditional infrastructure projects can help in augmenting the use of resources such as construction materials, water, energy and human resources. Once completed, digital technology can also help more effective monitoring and maintenance of projects by allowing developers access to real time data.

1 AIIB. 2020. Bringing E-Commerce to High Speed via Good Ground Infrastructure and Logistics. https://www.aiib.org/en/news-events/media-center/blog/2020/Bringing-E-Commerce-to-High-Speed-via-Good-Ground-Infrastructure-and-Logistics.html.

2 Financial Times. 2020. Online grocery delivery: an awakening (subscription access). https://www.ft.com/content/9a88acf8-8051-4b45-a59f-f49f0480e702; Amazon auditions to be “the new Red Cross” in Covid-19 crisis (March 31) https://www.ft.com/content/220bf850-726c-11ea-ad98-044200cb277f; Coronavirus: Southern Europe discovers digital shopping (subscription access). https://www.ft.com/content/26416b7a-6a89-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3; JD.com says delivery network will power it through coronavirus (subscription access).https://www.ft.com/content/015d956a-5c77-11ea-b0ab-339c2307bcd4;

3 International Telecommunication Union. 2012. Impact of Broadband on the Economy. https://www.itu.int/ITU-D/treg/broadband/ITU-BB-Reports_Impact-of-Broadband-on-the-Economy.pdf, and Jonas Hjort and Jonas Poulsen. 2019. "The Arrival of Fast Internet and Employment in Africa," American Economic Review, vol 109(3), pp. 1032-1079.

4 Huawei and Oxford Economics. 2017. Digital Spillover: Measuring the True Impact of the Digital Economy. https://www.huawei.com/minisite/gci/en/digital-spillover/files/gci_digital_spillover.pdf.

5 In some countries, such as Cambodia and Myanmar, fixed broadband internet penetration is low, but mobile internet penetration is high. Thus, they would be more resilient to the disruptions than what the figure appears to suggest in terms of other digital activities (e.g. online shopping, sales).

6 World Bank. 2017. Global Findex Database.

7 Chiou, L. and C. Tucker. 2020. Social Distancing, Internet Access and Inequality. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26982.pdf.

8 US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules—2017-2018 Data from the American Time Use Survey. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/flex2.pdf.

9 WFH-amenable sectors are defined by AIIB staff. These sectors are education, financial and insurance, public services, real estate, business and administrative work. Other sectors, which require face-to-face interactions, include accommodation, agriculture, construction, health and social workers, manufacturing, transportation and utilities.

10 Draft Digital Infrastructure Sector Strategy: AIIB’s Role in the Growth of the Digital Economy of the 21st Century. Available at https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strategies/operational-policies/digital-infrastructure-strategy/index.html.