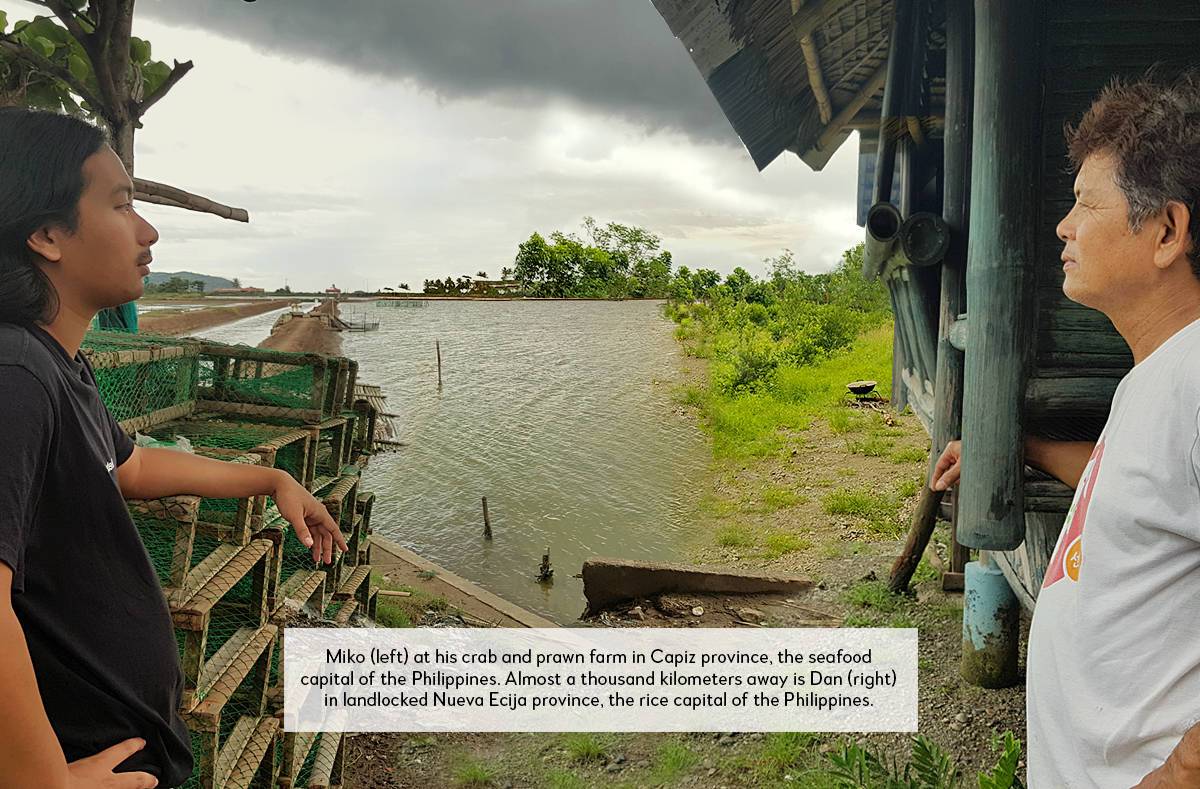

Miko Hechanova Ramos, 26, is conducting a technical assistance project in the city of Roxas in the province of Capiz. Embraced by the sea, Capiz is known as the seafood capital of the Philippines. Almost a thousand kilometers north is the landlocked province of Nueva Ecija where Dan Dimatulac, 58, is embarking on a development project to make a rice and vegetable farm sustainable. Nueva Ecija is known as the rice capital of the Philippines.

Two produce capitals in the same country—geographically and industrially distant and different. Two people far apart in terms of age and location. Yet Miko and Dan share something in common: they are leading their own respective development projects toward making farms sustainable.

“A lot of tacit knowledge is involved in aquaculture farming,” says Miko as we walked amid the 26-hectare network of ponds of giant mud crabs and “lukon” or giant tiger prawns, accessible only via small outrigger boats through the mangroves. As such, the knowledge Miko speaks of is difficult to transfer from one aquafarmer to another, unlike explicit knowledge that can be codified then shared to development workers worldwide.

On top of this challenge, various infrastructures at the crab and prawn farm need to be maintained or modernized. The four huge ponds are dependent on water gate and dike infrastructure. The dock and personnel housing need maintenance. There are various tanks for filtering, brooding and growing the crabs and prawns. Miko is considering the use of sustainable solar power in the hatchery and nursery which need 24x7 aeration, thus requiring constant electricity. Aside from sustainable energy, food for workers is also on the road to sustainability. Poultry have been raised and vegetables planted as food sources. There is also Miko’s plan on using “stressed crabs” as a sustainable food source for the farmers. They can predict which crabs will not survive the trip as they are transported, and since dead crabs are not bought, not eaten and are discarded after shipping, the farmers themselves can cook the stressed crabs not likely to survive the transport even before they die.

Miko’s technical assistance project is heavy on knowledge transfer. He is keen on improving feeding and water management, harvesting, packing and transport of crabs and prawns. He is also adopting vertical integration of the supply chain by cutting out middlemen through forward and backward integration.

Meanwhile, at the rice farm in Nueva Ecija, Dan has already used solar energy to light up the rice and vegetable farm at night. Like Miko, he has already planted and raised the farm’s supply of food. Like Miko, Dan’s rice farming knowledge is mostly tacit, but he is trying his best to share that knowledge. Like Miko, Dan is keen on helping improve water and irrigation infrastructure in the landlocked province of Nueva Ecija with the help of the local government. Like Miko, Dan has his own sustainable development project almost a thousand kilometers away.

Yet Dan and Miko share one other similarity as they lead their respective development projects and transfer their technical knowledge on sustainable farming: they are not development workers. Neither are they being funded by any development organization or multilateral bank—although such would no doubt vastly improve their infrastructure.

Miko is graduating with an MBA by the end of this year, and his technical, business and tacit knowledge are being transferred to his family and extended family of farm workers at home. Dan is also transferring his decades of knowledge on farm sustainability to his family.

Knowledge transfer on sustainable development starts at home. What more if this is augmented by infrastructure and development assistance?

Beijing, February 13, 2026

Enhancing Women’s Access to Public Services and Economic Opportunities through Rural Infrastructure in Cambodia

How AIIB financed rural road improvements in Cambodia are enhancing women’s access to healthcare, education, markets and livelihoods through gender responsive infrastructure and community driven planning.

READ MOREBeijing, February 12, 2026

Blending Policy and Performance: From CPBF to Downstream Investments

How AIIB strategically sequences and blends CPBF, RBF and IPF to turn policy reforms into bankable projects, mobilize private capital, and deliver measurable climate and development outcomes.

READ MOREBeijing, January 23, 2026

Strategic Portfolio Management Can Transform Development Finance. AIIB is Setting the Tone

The success of development finance lies not just in the projects approved but also in how they are delivered. As infrastructure needs grow and development challenges become more complex, multilateral development banks (MDBs) face not just an institutional mandate but a moral one – to ensure that projects deliver tangible impact to the millions they serve.

READ MOREBeijing, January 14, 2026

Supporting AIIB’s Mission through Sustainable and Effective Services

As AIIB enters 2026 and our second decade of operations, delivering sustainable infrastructure across regions depends not only on financing and partnerships, but also on the systems, services and spaces that support the Bank’s core business every day. The Facilities and Administration Services Department (FAS) plays a central and continuous role in enabling AIIB’s operational resilience, institutional maturity and people-first workplace culture.

READ MORE