What Are Stranded Assets and Why Are They Important?

Stranded assets are assets that have suffered from unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations, or conversion to liabilities. They are associated with the terms “economic loss”, “impairment”, “stranded costs” and “financial loss.”1

Recently, much public attention has been on the temporary or permanent stranding of assets as a result of a climate change event (e.g., a flood), or the rapid and disruptive low-carbon energy transition (e.g., renewables). Therefore, when investing in infrastructure today, it is essential to consider a wide variety of factors and scenarios, in both the short- and long-term, that could potentially lead to stranding during an infrastructure investment’s lifetime, and ultimately how to plan for and avoid it.

How should stranded assets be avoided or managed? Governments, companies and financial institutions should always attempt to measure and manage the exposure of infrastructure investments to external risks that can strand assets and internalize these risks in their decision-making and in their financial and economic models.

For example, central banks can play a critical role in raising awareness, preparing markets for the impacts of stranded assets and reducing investment in potential stranded assets. Recently, the Reserve Bank of India, Malaysian Central Bank and other central banks in Asia have started engaging on the topics of asset stranding, energy transition or climate change. More specifically, the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority has been assessing the exposure of the UK banking sector, estimated at GBP11 trillion (USD14.3 trillion), to climate change, to ensure adequate robustness and soundness of firms and enhance the resilience of the financial system.2 In November 2020, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Central Bank Governors and monetary authorities assessed the implications of climate and environment-related risks on both financial and monetary stability in the region. The study sets a series of non-binding recommendations including capability building and awareness, regulatory and supervisory framework, and surveillance and assessment framework.3

Overall, the perception of the risk of stranded assets depends on the time horizon of different investments. There is definitely a need for new tools to help better assess potential stranding as a result of climate-related physical and transition risks that will vary under different climate scenarios and differ by region, country and sector.

What Are Climate-Related Physical and Transition Risks?

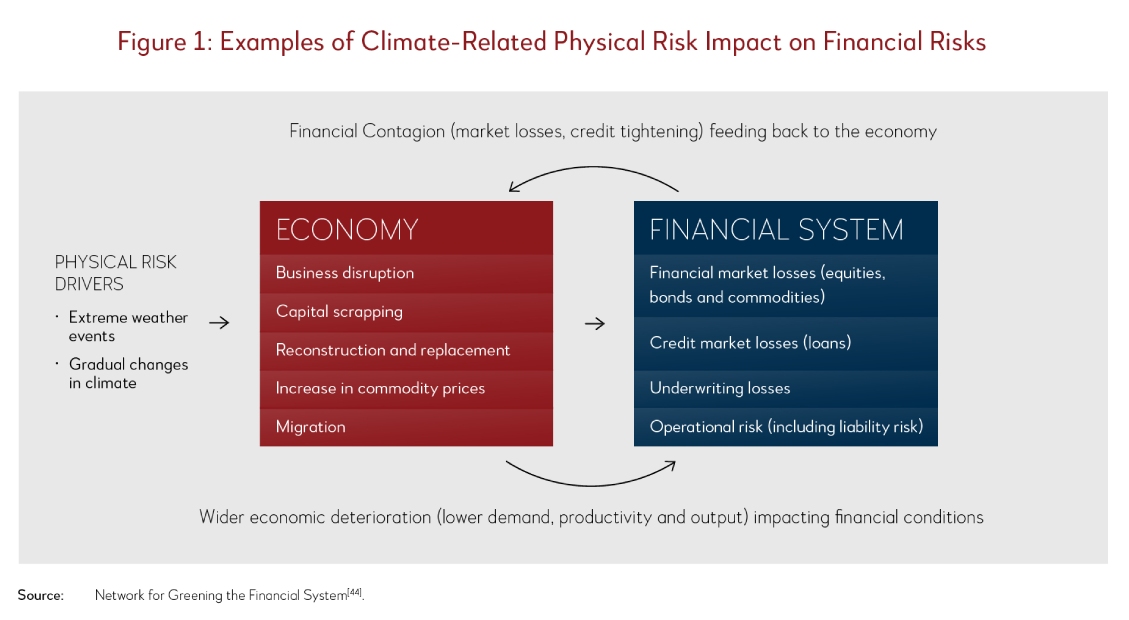

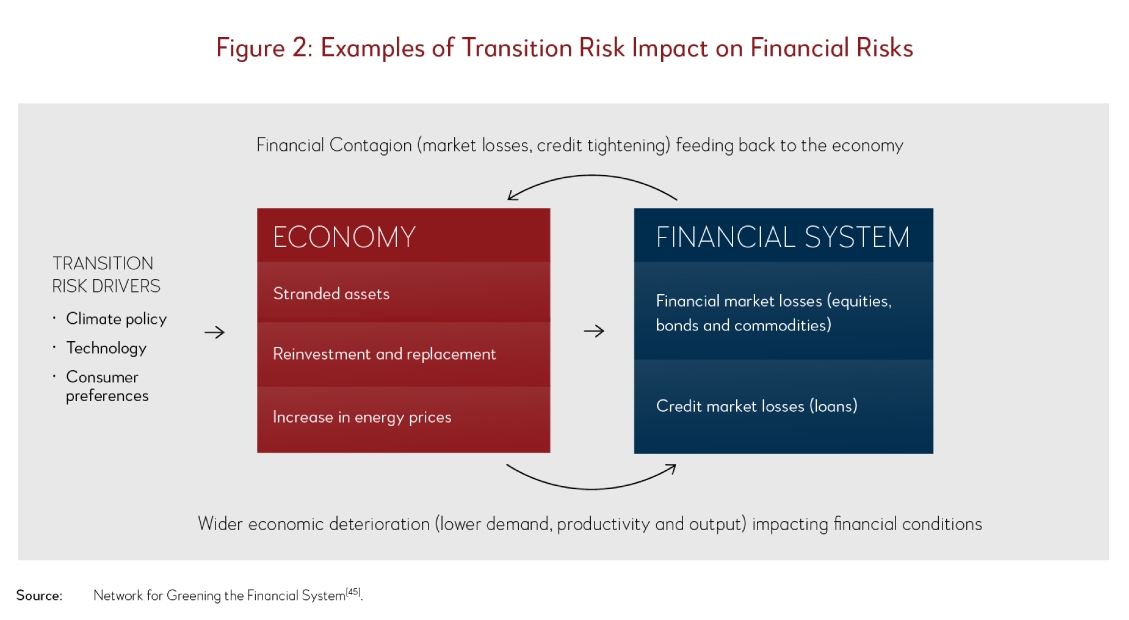

Every sector is likely to be impacted by some combination of climate-related physical (Figure 1) and transition risks (Figure 2), including agriculture, energy, forestry, and tourism. According to the Bank of England,

“physical risks are a result of climate and weather-related events, such as heatwaves, droughts, floods, storms and sea level rise. They can potentially result in large financial losses, impairing asset values and the creditworthiness of borrowers. Transition risks result from the process of adjustment toward a low-carbon economy. Changes in policy, technology and sentiment could prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets and create credit exposures for banks and other lenders as costs and opportunities become apparent.”4

In the energy sector, there are various transitional and physical risks that can lead to the stranding of fossil fuel infrastructure investments such as government policies (e.g., carbon pricing, air pollution regulations), financial (e.g., high fossil fuel prices, low-cost renewables), behavior (e.g., evolving social norms and needs) and environmental considerations (e.g., climate change, water scarcity, proximity to national parks), among many others.

Ultimately, renewable energy assets could also become stranded if impacted by extreme climate events such as typhoons, floods and droughts as well as disruptive technologies (e.g., even cheaper and more efficient solar photovoltaic panels, negative wholesale market prices). For example, rising temperatures in the Himalayas could increase glacier melts and potentially lead to landslides, lake outbursts, flash floods and even reduced water flows.5 Furthermore, in 2018-2019, severe droughts were experienced in Cambodia, Myanmar and Sri Lanka, which significantly affected hydropower production and led to regular blackouts. Overall, the level of financial impact will depend on the scale, pace and timing of the asset stranding.

Measuring Stranding Risk and Avoiding Poor Investment Choices

Methodologies for measuring stranded asset risks are still evolving rapidly and being improved. Most approaches are top-down and rely on reported data that is time-bound and quickly outdated, and sometimes insufficiently granular or incomplete depending on the countries and/or sectors being analyzed. For example, while the data available on the power sector is comprehensive, data availability is typically low for the construction and industrial sectors.

One possible approach is to go bottom-up through five steps of different degrees of complexity:

1. Gather project data.

2. Identify current and future risks and impacts.

3. Set scenarios and see how the risks and impacts change over time.

4. Assess how these risks and impacts will be managed.

5. Incorporate these risks and impacts in credit risk, valuation, and financial and economic models as appropriate.

This proposed approach allows a company or project sponsor to better understand and manage climate-related risks. The company can have the same fundamental risk exposure as its competitors but may have a lower risk because it has a plan and strategy to manage and mitigate such risks or ultimately divest.

Overall, the landscape for assessing climate risk, Paris Alignment and stranded assets is changing. Governments, companies and financial entities are increasingly committed and already dedicating resources and efforts to build a replicable model. However, consensus on the approach and methodology has been hard to achieve and therefore countries and organizations should set different thresholds and benchmarks suited to their needs. Therefore, a greater effort is needed to harmonize approaches to enable consensual and transparent decisions, while allowing for some flexibility. Governments, thought leaders and international stakeholders need to continue to foment further discussion and sharing of experiences in a constant pursuit for a common understanding.

AIIB, together with other multilateral development banks (MDBs) and international organizations, can play a leading role by working with the private sector to develop common tools and frameworks, and make these available to the wider public. Examples of AIIB’s projects supporting such discussions include the Asia Climate Bond Portfolio and AIIB Asia ESG Enhanced Credit Managed Portfolio projects. Furthermore, the joint MDB Working Group on Paris Alignment is considering applying shadow carbon pricing as a possible means to assess stranded assets, taking into account the climate risks (particularly the transitional risks) and their potential impact on the financial and economic viability of the project.

Once financial institutions see the value of having analytical frameworks and associated data systems that allow them to better assess and manage climate risks, Paris Alignment and stranded assets, the expectations are that these will build their internal capacity and expertise. The ones at the forefront of climate thinking will be the clear future winners.

This article is based on Chapter 5: “Planning for the Future and Avoiding Stranded Assets” of Asian Infrastructure Finance 2020: Investing Better, Investing More (AIIB and EIU, 2020), which discusses the importance of planning and avoiding stranded assets during the lifetime of an investment, with particular focus on the energy sector.

1 Caldecott, Tilbury & Carey. 2014. Stranded Assets and Scenarios. Discussion Paper. Smith School of Enterprise and Environment, University of Oxford.

2 Bank of England. 2018. Transition in thinking: The Impact of Climate Change on the UK Banking Sector. Bank of England‒Prudential Regulation Authority.

3 Bank Negara Malaysia. 2020. Report on the Roles of ASEAN Central Banks in Managing Climate and Environment-related Risks. https://www.bnm.gov.my/-/report-on-the-roles-of-asean-central-banks-in-managing-climate-and-environment-related-risks.

4 Bank of England. 2018. Transition in Thinking: The Impact of Climate Change on the UK Banking Sector. Bank of England‒Prudential Regulation Authority.

5 Bank aus Verantwortung. 2021. Climate Change‒Glaciers under Surveillance. June 4. https://www.kfw.de/stories/environment/climate-change/glacier-monitoring-pakistan/.