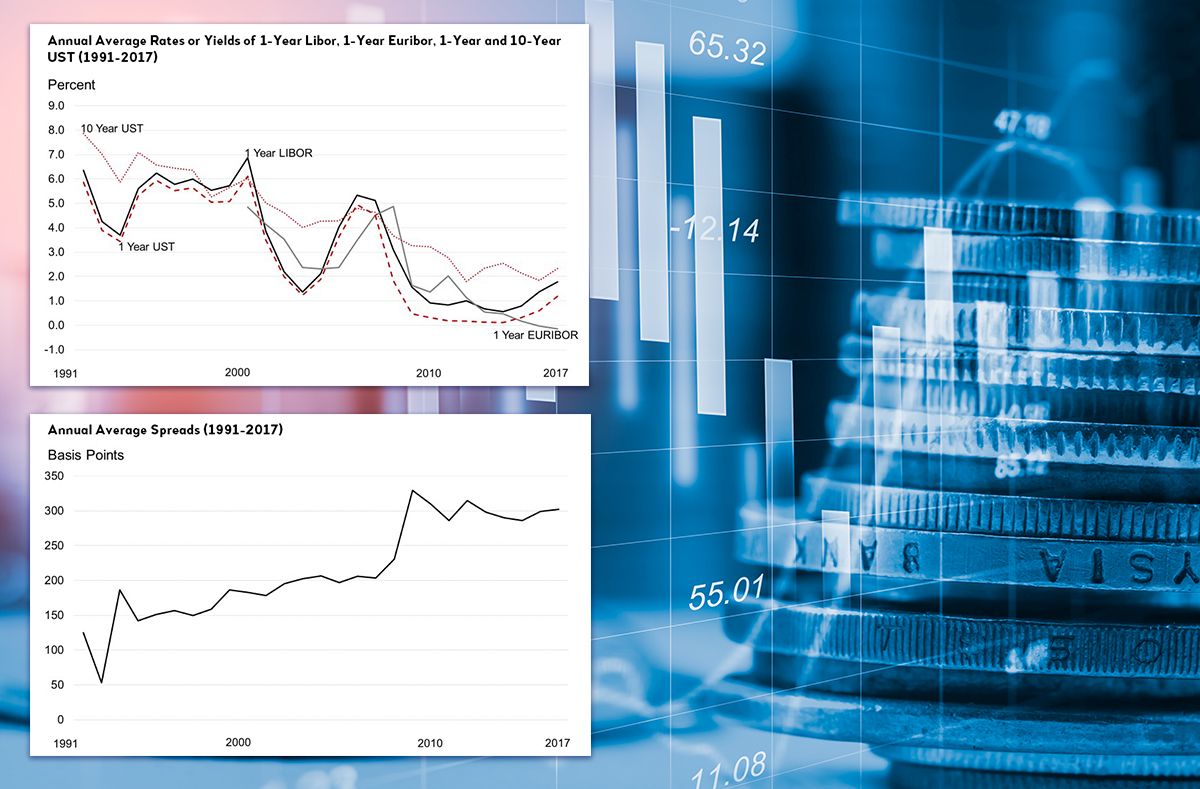

The syndicated bank loan market is a very important one for corporate finance, including for project development. Each year, more than USD5 trillion worth of credit is channeled through this market. Banks come together (in a syndicate) to provide financing to large projects and to diversify risks. For loans, banks would charge a spread above their funding cost, usually taken to be LIBOR.

I have noticed and have been wondering about this for some time. Why are private sector bank loan spreads so elevated, even though central banks have held interest rates down and even when the banking sector is flushed with reserves through quantitative easing?

This is not a trivial issue. The divergence between government yields and private loan spreads means that while governments can borrow cheaply, the private sector might be facing higher borrowing costs.

Higher spreads obviously affect private investments, including for infrastructure. More generally, this is also related to what I loosely call the Blanchard and Mankiw debate—the former argues that fiscal policies are nearly costless given the low government borrowing costs, while the latter argues that government spending will come with distortions.

Basel regulations affect higher banking loan spreads, and there is undeniably some impact. Still, spreads seem too high to be solely explained by regulations. In a paper published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics and Finance, I examined if larger fiscal deficits have a crowding-out impact through the private sector loan channel.

The answer is yes, larger deficit spending by governments (the United States in particular) do seem to have an upward impact on private sector credit spreads. This could be due to the government competing with the private sector for funding and, to a certain extent, higher perceived risk. We cannot think strictly in terms of the traditional deficit and government bond yield angle since government yields are now held very low by aggressive monetary policies (quantitative easing) postcrisis.

The interesting angle in this research is that it makes use of an important feature in the loan market, where borrowing costs are recorded in two separate components (1) the reference rate, which is usually LIBOR and (2) spreads over LIBOR. The research focuses only on the second component which frees it from possible confounding factors (such as the actions of central banks), giving more confidence to the results. On average, one percentage point to gross domestic product increase in government deficits lead to a 9-basis-point increase in spreads and a reduction of loans by around half the magnitude of the deficit.

There are several policy implications. First, fiscal consolidation can be helpful in bringing down private sector loan rates. To the extent that lower private sector spreads can spur more investments, fiscal consolidation does not need to be seen as contractionary for economies. Second, US deficits will have a spillover impact on even non-US loans. This is something developing economies will have to watch and make buffers for. Third, country ratings do affect private sector loan spreads—any downgrades will make private sector loans more costly.

As we look forward to having more private sector investors help fill the infrastructure gap, it is also important to establish prudent macroeconomic policies that do not lead to the crowding-out or rise in risks to the private sector.

Given the more elevated spreads, one way to reduce this is to have more syndication between banks. The study also shows that by sharing risks, spreads can be reduced. In this regard, AIIB will be keen to partner with banking institutions to provide syndicated loans and catalyze more private sector capital into infrastructure development.