An unintended consequence of COVID-19 has been a collapse in oil prices. Amidst low demand and uncertainty, West Texas Intermediate, the US oil benchmark, slumped to negative USD37.63 per barrel (pb), below zero for the first time in history. However, OPEC is set to reduce production in May and oil prices are expected to rebound—the July and August contract prices are a testament. But low prices are expected to persist as futures for oil are below USD40 pb as far as late 2024. These developments and forecasts have experts worried about many things, one of them being the impact on renewables.

True, there are currently more pressing problems for renewables: lockdowns, supply chain disruptions, liquidity crunch, and uncertainty over future electricity demand, among others. Construction delays may also prevent projects from qualifying for various public incentive schemes. Once the pandemic crisis is resolved, however, these issues will be largely ironed out. But low oil prices? What will they do to renewables?

It may seem like cheap fossil fuels make renewables less attractive and reduce economic incentives for energy efficiency. By this logic, renewable energy projects should become less profitable and may even stall. But if history is any guide, this does not have to happen—despite an oil price crash in 2014-2015, renewable energy investment has had a historic run. Factors then at play are now even stronger.

First, oil is not a direct competitor. Oil is not the predominant fuel source for power at the global level. While there will be an indirect impact through spillovers to gas prices, the viability of renewables for power generation is not directly affected by oil prices.

Second, investment in renewables is now driven by national policies and long-term commitments, including Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement and national renewable energy targets and policies, which are not affected by oil prices. For instance, India, China, and Morocco have committed to source a certain proportion of their energy from renewables or add renewable capacity. India has committed to building 175 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy capacity by 2022 under its National Electricity Plan. China has also committed to sourcing 20 percent of its total energy needs by 2030 from renewables. Morocco, on the other hand, plans to source more than 50 percent of its electricity requirements from renewables by 2030. Further, domestic policies, like China’s shift from a subsidy to an auction system, or India’s renewable purchase obligation, have larger impact on renewable energy investments than oil prices.

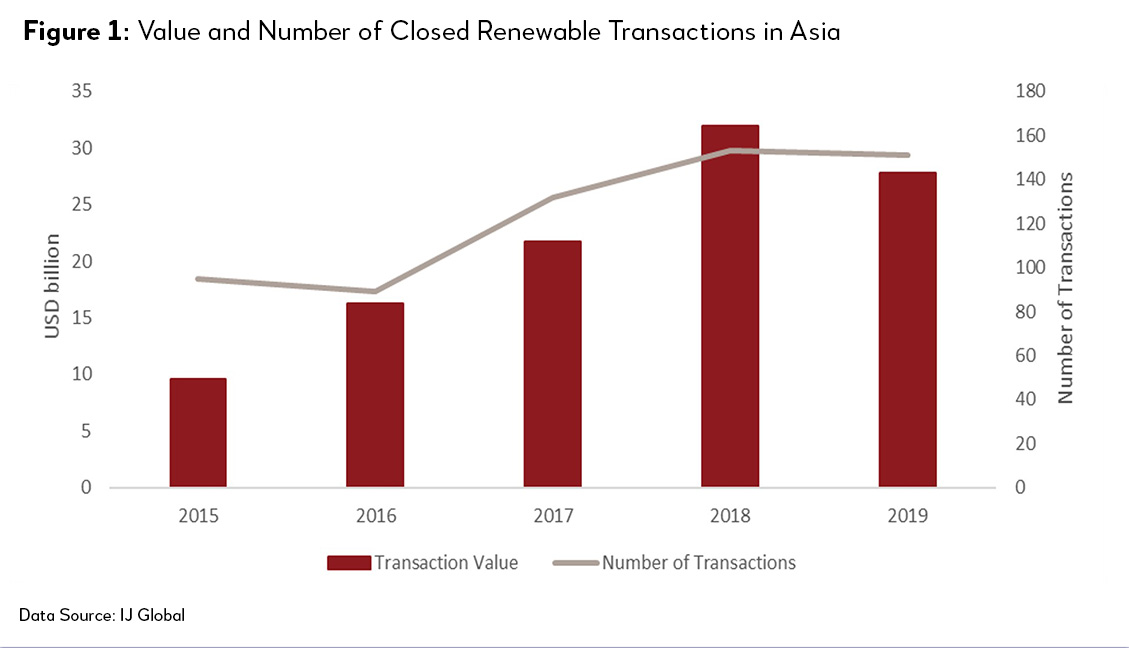

In fact, the renewable industry in Asia has seen tremendous growth recently (Figure 1). The value of closed transactions had increased by more than 300 percent from 2015 to 2018. During 2018-2019, 279 renewable projects worth USD95 billion have been announced or bid out. Thus, one would certainly expect to see more financial closures in the coming years, as soon the pandemic is contained.

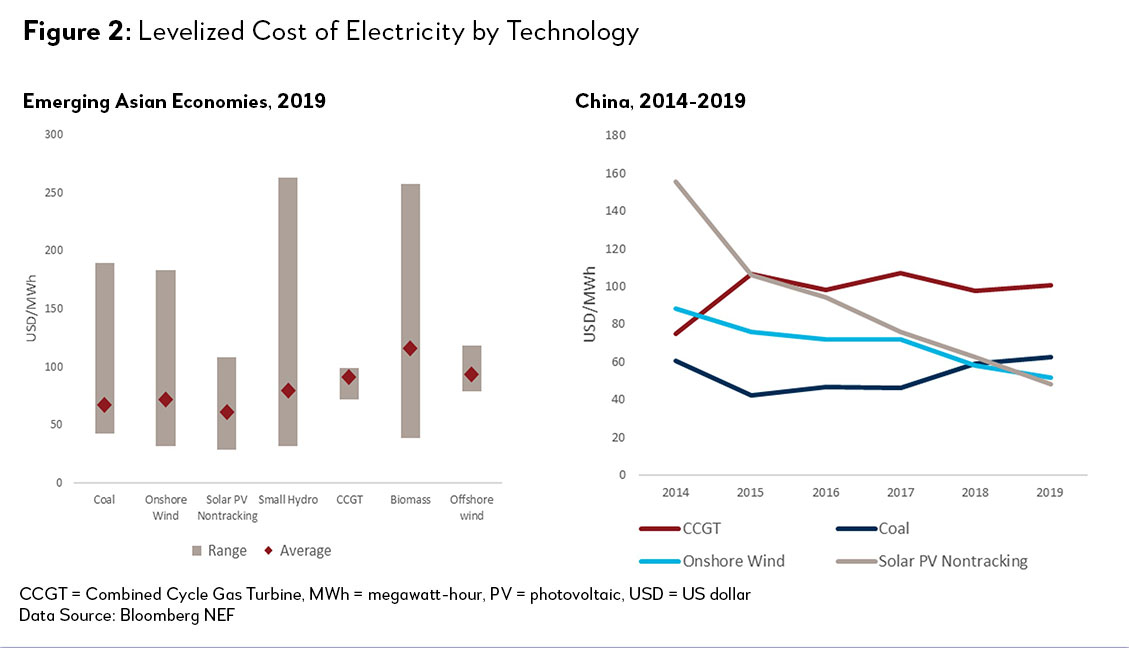

Third, cost reductions have played an important part. Hydropower, solar and wind are already cost-competitive or cheaper than fossil fuel power generation in several countries (Figure 2) and many governments increasingly prioritize investing in them. Technological progress in renewables is likely to continue, while efficiency gains in fossil fuel technology has been largely exploited.

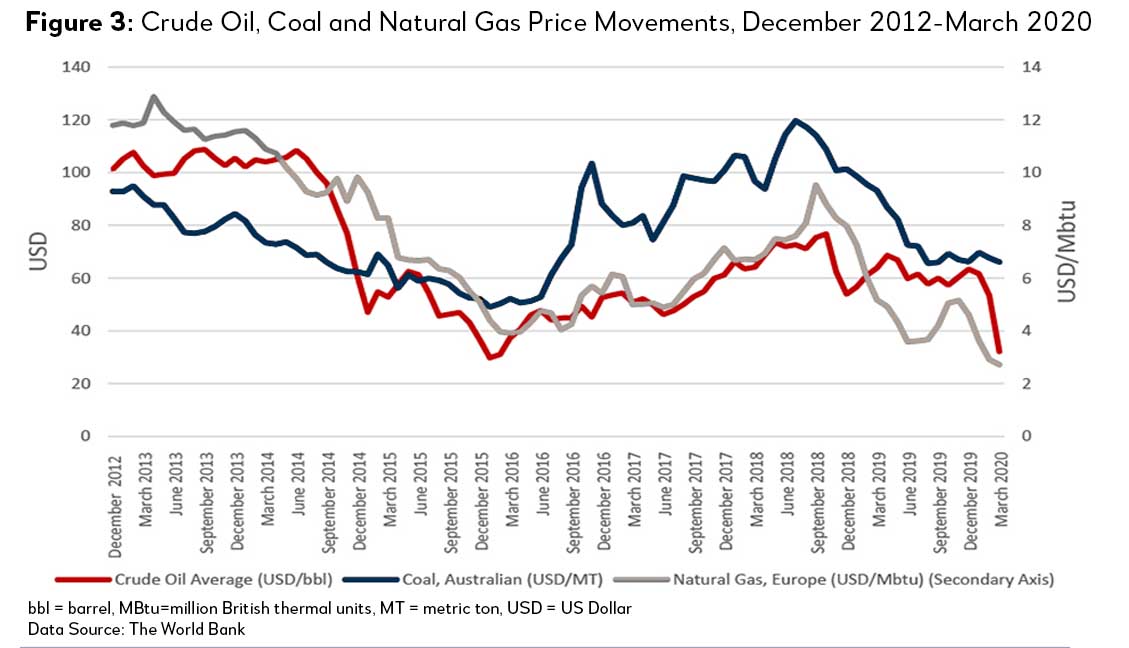

Low gas prices help in the transition, for now. Although gas markets are fragmented and prices vary, gas prices are indexed to oil prices (with a lag) in many markets. Hence, a decline is to be expected. There might be some exceptions as drillers could move away from oil to gas or high-cost oil fields might go bust. All things being equal, lower oil prices almost invariably correlate with lower prices of natural gas. Of course, renewable projects may be less competitive vis-à-vis natural gas power, but coal has a more interesting angle.

Sustained low natural gas prices could drive a switch from coal to gas in power generation. While not as clean as renewables, gas is cleaner than coal, and could play a role in the transition to a low-carbon energy mix. In 2019, the average levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) per megawatt-hour (MWh) for coal and natural gas were around USD60/MWh and USD90/MWh, respectively for emerging economies. The average monthly prices of crude oil and natural gas in Europe then were USD61.4 pb and USD4.8/Mbtu, respectively. As natural gas prices decline, so should the LCOE.

This, of course, depends highly on the price of coal, which has also been declining (Figure 3). It seems that coal prices may remain low until demand picks up. However, in the medium to long term, if low oil prices and gas prices are sustained, gas could become a viable alternative for coal, primarily for countries that are increasingly using coal for power. Yet, government policies can tip the balance toward coal again, particularly if they prioritize or subsidize coal, such as in seen many coal-producing countries.

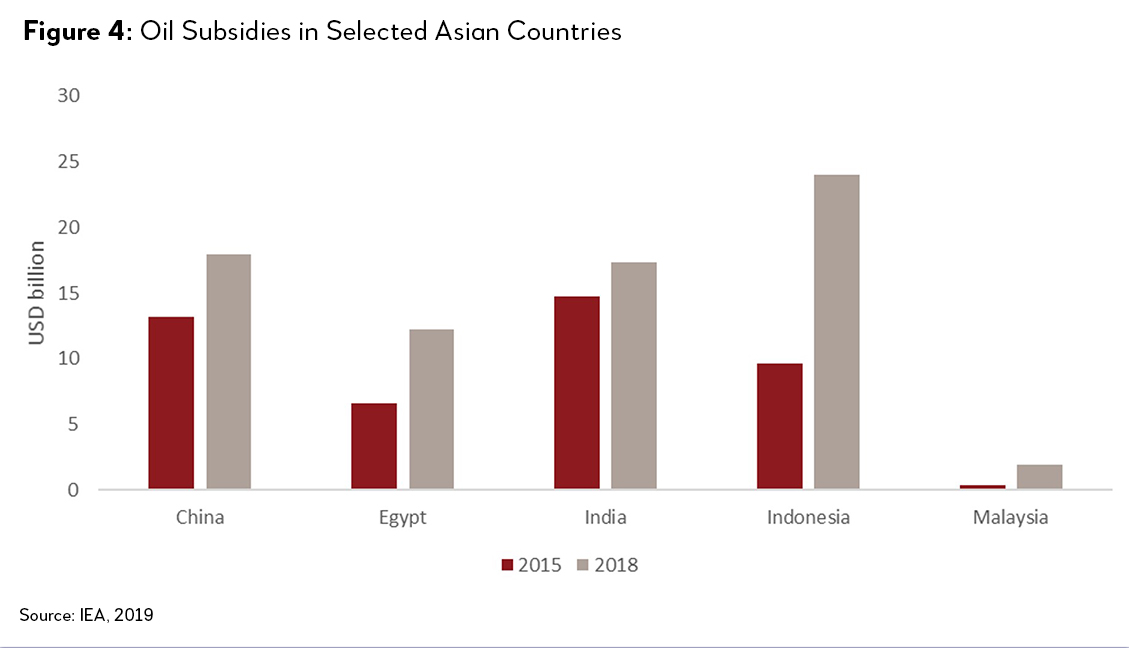

An opportunity for reforms. This is also a unique opportunity for the many countries that subsidize fossil fuel (see Figure 4) to remove billions of dollars in such subsidies, and thus reduce wasteful fuel consumption. That would perhaps be the single most important action on their clean energy transition agenda, locking in fiscal savings and lower emissions. Given the low oil prices, such move can be politically supportable.

Fossil fuel energy may be cheap now, but fossil fuel projects are becoming ever riskier. We have just observed a second massive oil price collapse in just six years. This, coupled with a rising long-term trend of carbon-conscious investing and mounting worries that many planned fossil-fuel projects may become prematurely unviable (stranded), certainly improves the risk-return profiles of renewable vs. fossil-fuel projects. Renewable projects are also protected by long-term purchase commitments. Their non-dispatchability and preferential status could help them weather power demand volatility. For example, in China in early 2020, solar and wind power generation rose amidst declining power demand.

Strong need to maintain momentum on renewable investments. At the policy level, COVID-19 has relegated climate change to the back seat. At the project level, pervasive uncertainty and liquidity shortages have put financing and refinancing of many projects at risk. At the macroeconomic level, countries will emerge from the pandemic with much weakened fiscal positions and there may be pressure to reassess the level of support they provide to renewables.

We must not lose sight of climate change targets. First, in the short term, economically viable renewable projects must not be allowed to fail for lack of liquidity or funding. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are well positioned to offer countercyclical support in the form of financing or refinancing for both public and private sector projects in order to restore and/or enhance viability where needed. Second, once the pandemic emergency is contained and economies stabilized, there likely will be a need for a stimulus—this could be designed to promote energy efficiency and green investment or, at least, to not bail out carbon-intensive assets that may soon become stranded anyway. Third, the potential for coal-to-gas transition could be assessed, where appropriate.

The possibility of the pandemic was well articulated long before this crisis, but it was hard to galvanize policy actions towards a tail end risk. Many countries were thus unprepared. We need to work together to ensure that climate change risks are properly dealt with as there would be no excuse to say we didn’t see the risks coming.

References:

1. CME Group. 2018. Are Crude Oil & Natural Gas Prices Linked?

2. IEA, 2019. World Energy Prices.

3. Bloomberg NEF. 2014. Oil Price Plunge and Clean Energy.

4. Bloomberg NEF. 2020. Liebrich: Covid-19—The Low-Carbon Crisis.

5. Thompson, Gavin. 2020. Oil Price Crash: Where does Asia Go from Here. Wood Mackenzie.

6. Bloomberg NEF. 2020. After Two Bad Winters, Natural Gas Heads for an Even Worse Summer.

7. Bloomberg NEF. 2020. Covid-19 Could Destroy 26% of Gas-to-Power in Europe.

8. Bloomberg NEF. 2020. Coal is the Most Expensive Fuel after Oil’s Brutal Collapse.

9. Hallmayer, et al. 2015. How Lower Oil Prices Impact the Competitiveness of Oil with Renewable Fuels. Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy.

10. McNally, Robert. 2020. Oil Market Black Swans: Covid-19, the Market-Share War, and Long-Term Risks of Oil Volatility. Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy.

11. IEA. 2020. Energy market turmoil deepens challenges for many major oil and gas exporters.

12. IEA. 2020. Tracking the impact of fossil-fuel subsidies.

13. IEA. 2020. The global oil industry is experiencing a shock like no other in its history.

14. IEA. 2020. Energy market turmoil deepens challenges for many major oil and gas exporters.

15. IEA. 2020. The coronavirus pandemic could derail renewable energy’s progress. Governments can help.

16. IEA. 2020. Oil Market Report—March 2020.

17. Parnell, John. 2020. Could the Oil Price Collapse Drive More Investment into Renewables? Green Tech Media.

18. Financial Times. 2020. Oil shock threatens to take wind out of sails for renewables shift.

19. Fitch Solutions. 2020. Majors Rollback Capex as Oil Price Plummets.

20. Owens, Josh. 2020. Is the Oil Price Crash Good for Renewable Energy? Oilprice.com.

21. Gowdy, Johnny. 2015. Oil Price Collapse—not all bad news for Renewable Energy. Regen.

22. Hallegatte, et al. 2020.Thinking ahead: For a sustainable recovery from COVID-19 (Coronavirus). World Bank Blogs.

23. Smart Energy International. 2020. Renewables set to win during China’s COVID-19 lockdown.

24. Zhang, et al. 2019. Does oil price uncertainty affect renewable energy firms’ investment? Evidence from listed firms in China. Finance Research Letters.

25. Tabner, et al. 2015. Why falling oil prices should not undermine investment in green energy. The Conversation.

26. Rathi, Akshat. 2020. Green Energy’s $10 Trillion Revolution Faces Oil Crash Test. Bloomberg.

27. Financial Times. 2020. US shale bust wrecks hopes for energy independence.

28. Financial Times. 2020. Oil industry faces biggest crisis in 100 years.

29. Financial Times. 2020. Coronavirus hits home; Oil shocks threaten green investments; EU carbon tax plan falters.

30. Financial Times. 2020. Eight days that shook the oil market—and the world.

31. Raval, Anjali 2020. Can the world kick its oil habit? Financial Times.

32. Nyquist, Scott. 2015. Lower oil prices but more renewables: What’s going on? McKinsey & Company.

33. Mountford, Helen. 2020. Responding to Coronavirus: Low-carbon Investments Can Help Economies Recover. World Resources Institute.