As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds across the world, infrastructure development has undoubtedly been impacted. However, timely consolidated data on infrastructure developments and sentiments are often lacking. Conventional data series will come with a long lag.

This research explores some unconventional data—online textual information—to track the economic impact of the outbreak. In a time of crisis, getting timely data of the latest developments is more important than ever. Specifically, this analysis searches for key words in a news archive database to identify online media reports related to COVID-19 disruptions, such as the suspension and cancellation of infrastructure projects, as well as infrastructure stimulus. Then it examines how many reports are associated with these keywords during the outbreak, to understand the extent of its disruption. In addition, these results are compared and validated with other sources, such as project data and textual information in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) COVID-19 Policy Tracker.1

Suspension and Cancellation Announcements Peaked in Late March in Asia

Right after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 12, 2020, many countries started adopting lock-down policies to various degrees. Construction has been one of the most disrupted sectors aside from entertainment, as it is highly dependent on labor and the supply chain of building materials. Infrastructure projects can also be sensitive to financing conditions, with projects finding it hard to obtain finance during a crisis.

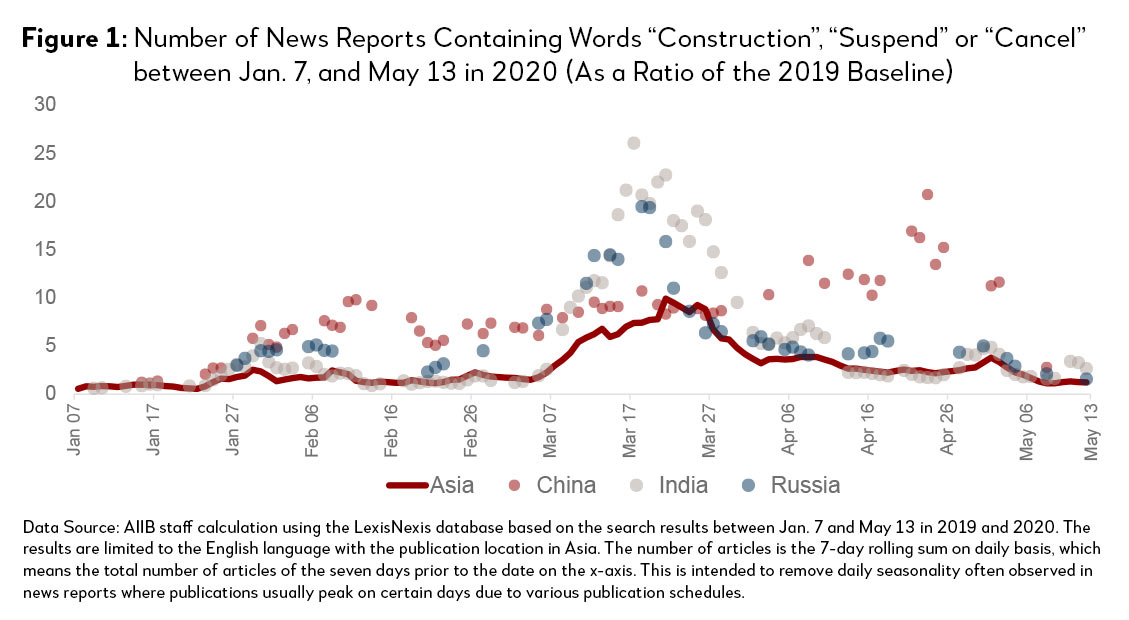

These disruptions can be seen in the surging number of news articles related to this topic during the outbreak. In Figure 1, the number of news articles with “Construction”, “Suspend”, or “Cancel” are compared to the baseline in 2019. Before the lockdown in Wuhan on Jan. 23, 2020, the ratio of the number of news articles published in 2020 (compared to the 2019 baseline) stayed around 1 (i.e., there was not much change in construction sentiments). After that, this ratio jumped to 10 in early February for China. Until the end of February, this ratio was also relatively close to 1 for the rest of Asia.

In early March, the number of news reports on construction suspensions or cancellations rapidly climbed in Asia, particularly those published in India where the amount was more than 20 times what it was in 2019 for the same period. At its peak, Asia saw seven times more articles in late-March 2020 than in 2019, more than a week after the WHO declaration. These results indicate that disruptions to construction and other production activities escalated to a global level as early as March.

As of May 13, the number of reports flattened to pre-outbreak levels, suggesting that suspensions and cancellations gradually cooled down as COVID-19 gradually came under control in many Asian countries.

Cancelled Constructions Mostly Power Infrastructure in India and China

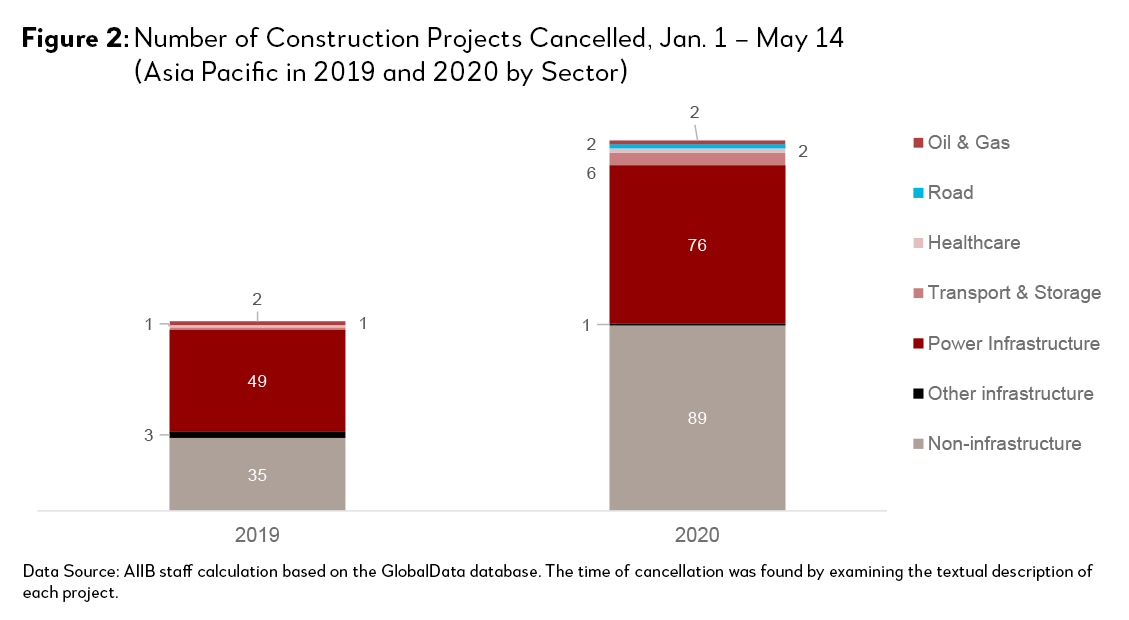

Further analysis was done by sector and by geography, using detailed text documentation of the GlobalData database.2 From Jan. 1 to May 14, 2020, 178 projects in the Asia-Pacific region were reported to be cancelled, almost doubling the number of 2019 (91 cancelled) using the same time range.

As shown in Figure 2, 42 percent (76) of them were power infrastructure, particularly in wind energy (27), solar (21) and coal (15). Among non-infrastructure constructions, the most affected were manufacturing plants, where 29 construction projects have been cancelled from January to May 2020. In particular, the power sector seems to be very sensitive to external shocks: from early-January to May of 2019, half of cancellations were dominated by projects in this sector.

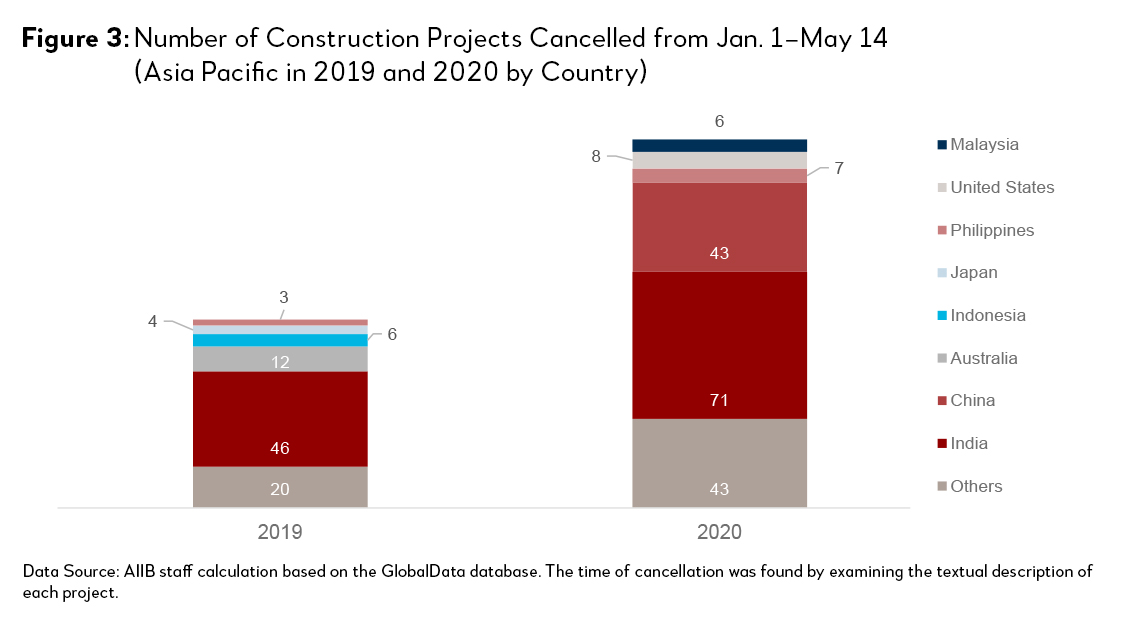

Geographically, 40 percent and 24 percent of cancellations were announced in India and China respectively (Figure 3).3 In China, the number of cancelled projects jumped to 43 during January-May in 2020, compared to only 2 projects reported in 2019 in the same period. There was also a significant increase in the number of canceled constructions in India, from 46 in 2019 to 71 in 2020. After China and India, Philippines saw seven projects cancelled, four more than in 2019.

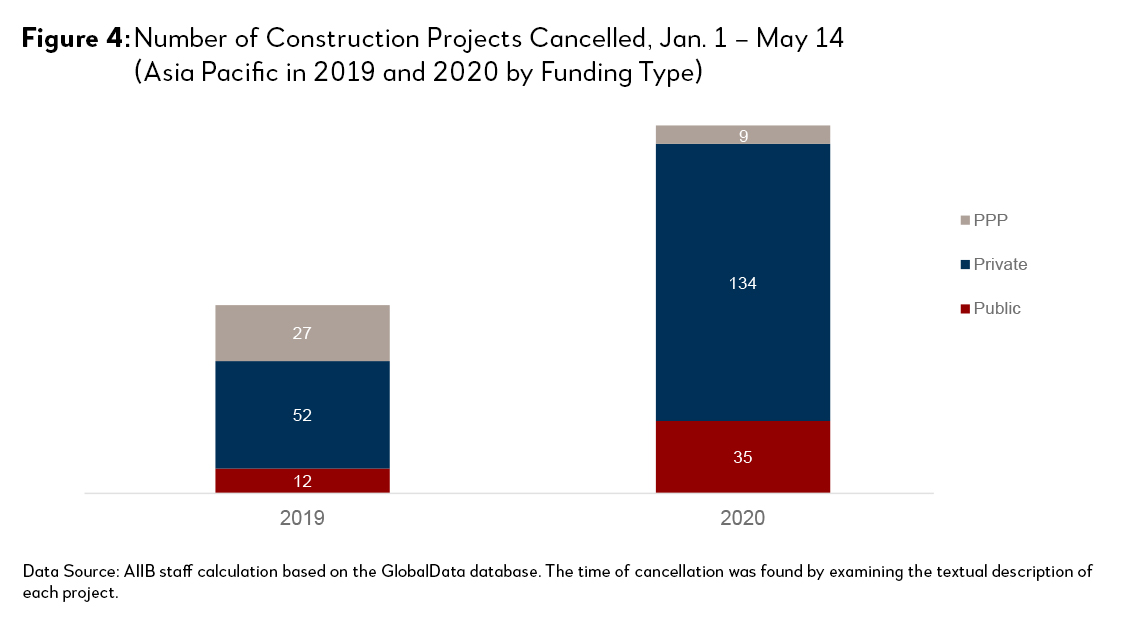

Disruptions to privately funded projects were much worse than public or public-private partnership (PPP) projects in the Asia Pacific (Figure 4). Three-quarters of the cancelled projects were privately funded, the rest were either public or PPP. In the same period in 2019, cancelled projects were mainly private sector too, but the share was smaller (57 percent).

Infrastructure Stimulus Has Become a Key Topic

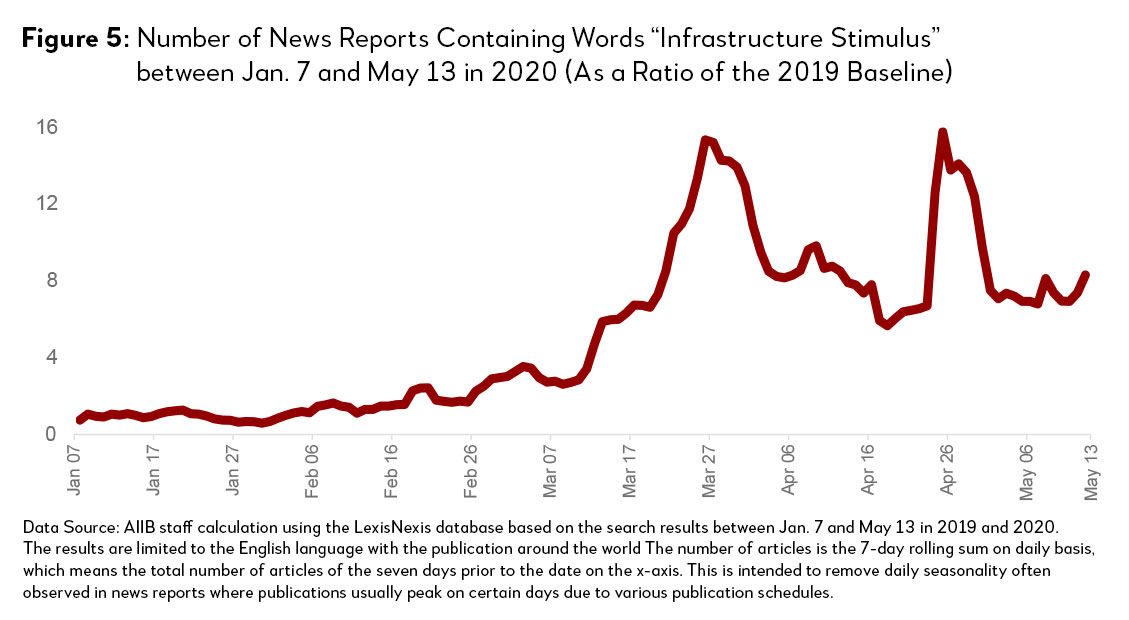

While the economic disruption is not in doubt, there are signs that policy makers and investors are looking past the crisis. Boosting investment in infrastructure has long been seen as a countercyclical measure. This time is no exception. Using the phrase “infrastructure stimulus” as a search key word, it turns out discussion about this topic has become increasingly frequent (Figure 5). After a peak on March 27, the topic cooled down, but still remained four to eight times its popularity in April 2019. It peaked again on April 26, likely due to the fact that many economies released 2020 Q1 economic indicators by this date.

Lower-Income Countries Focus More on Fiscal Investment in Health than Higher-Income Countries

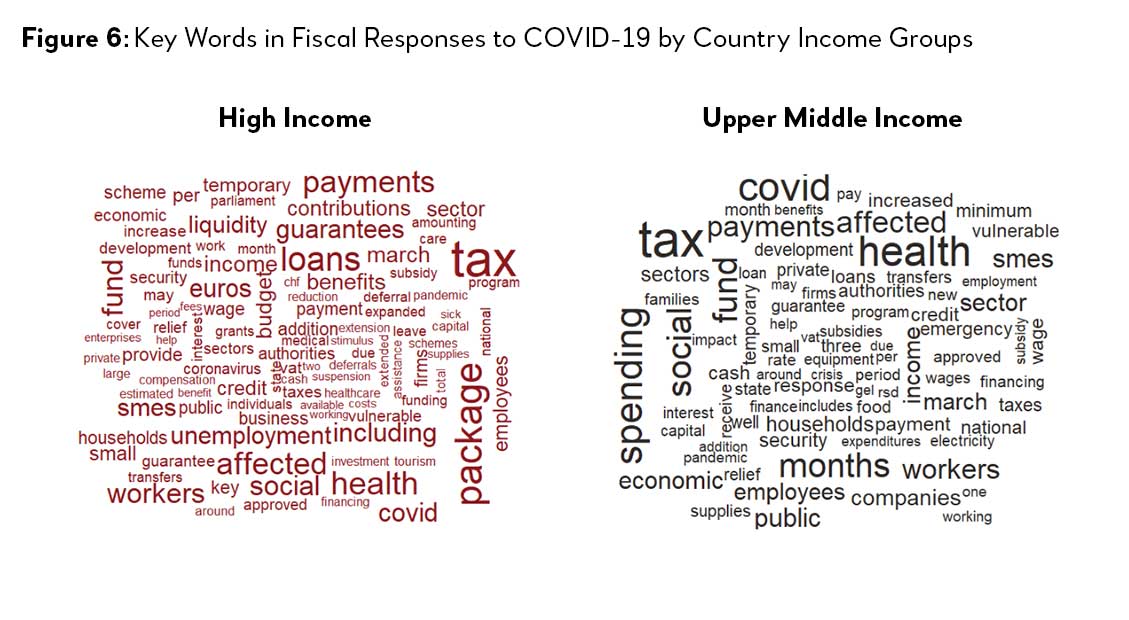

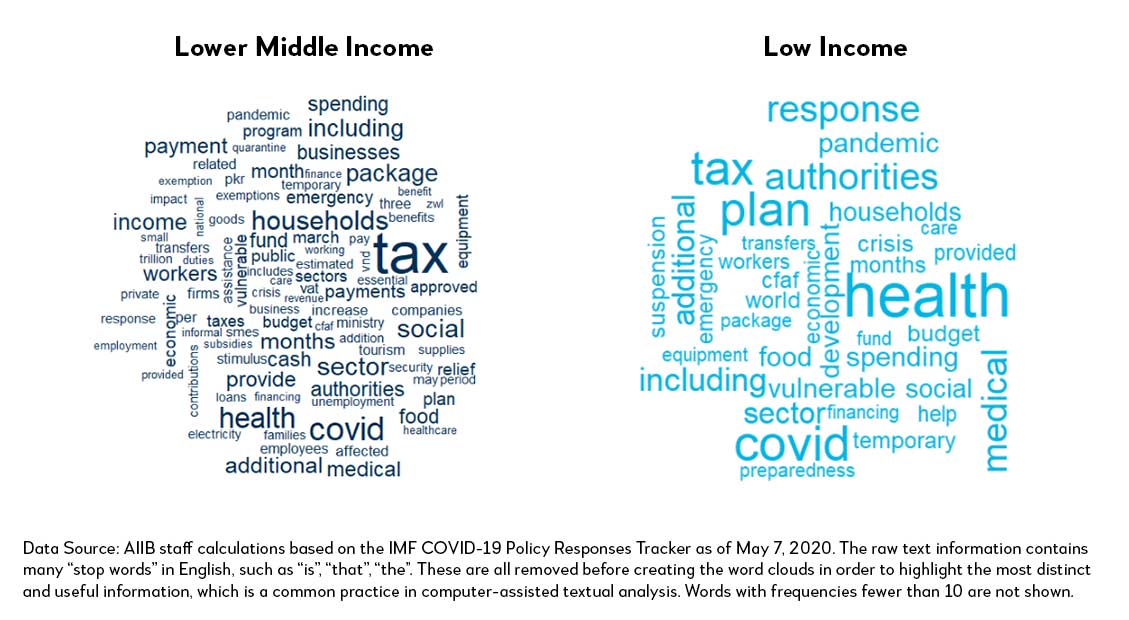

In response to the pandemic, fiscal policy packages across the world may have different priorities, depending on the various needs of countries. Analyzing textual information updated by the IMF on its Policy Responses to COVID-19 webpage, interesting differences also show up in policy responses.

As of May 7, 2020, at least 38 IMF members started or discussed plans to reopen their economies.4 Most of IMF’s members have also developed fiscal policies to contain the pandemic and protect vulnerable populations. Figure 6 shows the most frequently mentioned words across countries from low to high-income levels.

Interestingly, it appears that low, lower-middle and upper-middle income countries all highlighted the word “health”, followed by other words such as “social” and “medical”. Meanwhile in high-income countries, the message is mixed, but it looks like the key words are more associated with unemployment protection, including “unemployment”, “guarantee”, “benefits”, and “workers”.

Such differences reveal distinctions regarding the fiscal policy priorities between high and low-income economies: in both groups, negative shocks leading to rising unemployment may be shared concerns, but since low-income countries have more fragile health infrastructure systems that have been overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases, they tend to seek immediate support for their medical systems more urgently than high-income countries. It is likely that this pandemic has served as wake-up call for lower-income countries to realize how insufficient investment in health facilities could and did have rippling consequences on the economy, especially in the time of a global pandemic.

Big Data Can Help Inform Policy and Policy Designs

The application of text mining techniques can help unearth useful insights from some unconventional data sources. By examining news reports and filtering websites using key words, this research has identified signals of the changing situation of COVID-19 disruptions and policy responses across countries in infrastructure development.

In today’s world, information is no longer limited to well-organized and structured datasheets that take painstaking efforts and often a long time to construct. For example, economists have used news articles to measure market sentiment to understand the US economy, and the results turned out to be as useful as the sentiment measures constructed from conventional household surveys.5 With proper design and technology, unstructured data, which is often called “big data” and can come from such sources as electronic documents, online websites/comments and other forms of seemingly messy files, can be transformed and analyzed to gain useful policy insights in a timely manner.

1 The IMF Policy Responses to COVID-19 webpage tracks the latest fiscal, monetary and exchange rate policies of governments in response to the pandemic. See https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19.

2 GlobalData database has a global construction project database that documents detailed information of the project, such as location, time of announcement and a log file that records every major incident associated with the project. We identified the cancelled projects that were reported to be cancelled between January 1 to May 14 in 2019 and 2020 by (1) filtering out the projects with the status of “cancelled”; (2) further narrowing down the list to only include projects that were reported to be cancelled between Jan. 1 and May 14 in 2019 and 2020 by checking the date of cancellation in the log file.

3 The locations of these projects are assumed to be the “key country contact” variable in the GlobalData database.

4 AIIB staff calculation by scraping the IMF Policy Responses to COVID-19 webpage and manually counting the economies that have discussed reopening plans as of May 7, 2020, per the “Reopening the Economy” section.

5 A.H. Shapiro, M. Sudhof and D. Wilson. 2017. "Measuring News Sentiment," Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2017-01. Available at https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2017-01.